The commonly accepted way to think about infrastructure is to consider it as the support systems that enable the existence and routine operation of other things. It can take many forms: physical (hard infrastructures like sewers, water mains, streetlights, roads, bridges, etc.), social (education, health care, welfare programs of many kinds, etc.), epistemic (rules, regulations, laws, established protocols, best practices, standards). What all of these things have in common is that they have duration and allow for the repetition of certain tasks—over and over and over again—in relatively the same way each time.

Education is actually far more than a social infrastructure system—for it to operate as such it is underpinned by the other kinds of infrastructure (physical = schools and busses; social = contracts between school districts and teachers/administrators; epistemic = pedagogical practices, adopted curricular materials including standards, etc.).

The only thing that is dangerous about this thinking is that infrastructure can be just about anything that performs a service in service to something else (I call this “infrastructure universalism”.) Any subservient thing, idea, or even person can be “infrastructural.” Nevertheless, the concept of infrastructure is a great way to start disentangling the complexity within something as big and multifaceted as “the education system.”

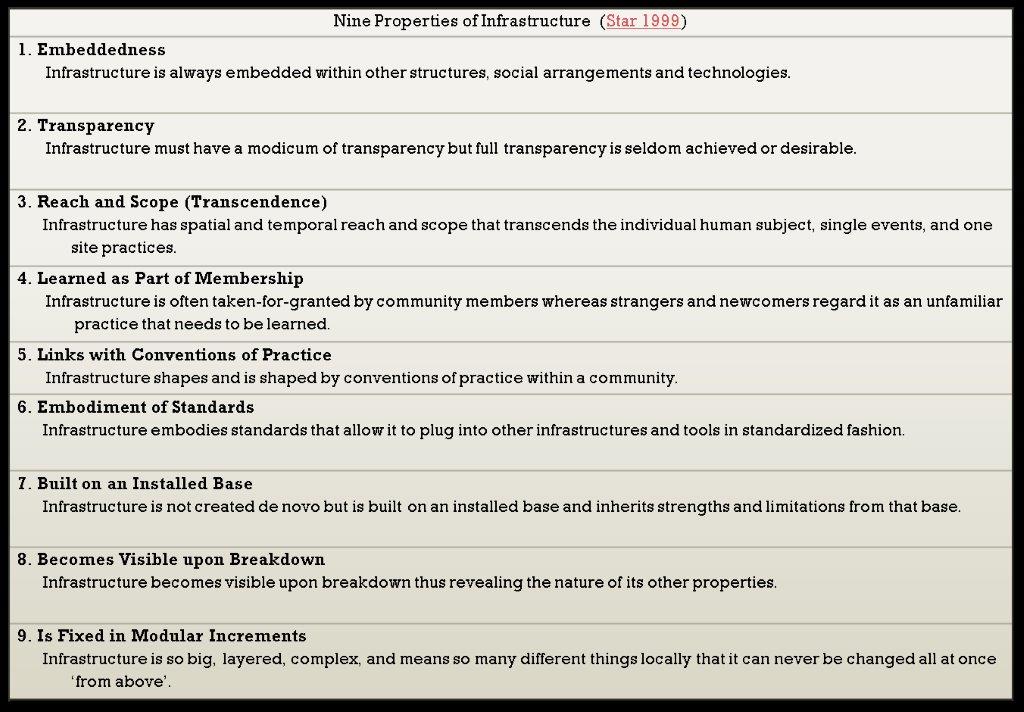

My view of education as multi-faceted infrastructures has been influenced by Susan Leigh Star’s article “An Ethnography of Infrastructure” (American Behavioral Scientist November 1999 vol. 43 no. 3, pp. 377-39). In it, she proposed 9 properties of infrastructure. Star’s properties are important because they are “multi-relational” and—therefore—inherently spatial and suggestive of geographical relations, too.

For example: Property #4. School children are indoctrinated into certain rules and regulations regarding behavior. If a child changes schools, they need to learn the rules that are particular to the new school. If they have trouble learning these rules, they may get warnings, detentions, suspensions or expulsions. If they come from a school with more stringent rules, they may be held up as a “model student” in the new school because of the regimentation that they carry with them from their prior learning environment.

For example: Property #4. School children are indoctrinated into certain rules and regulations regarding behavior. If a child changes schools, they need to learn the rules that are particular to the new school. If they have trouble learning these rules, they may get warnings, detentions, suspensions or expulsions. If they come from a school with more stringent rules, they may be held up as a “model student” in the new school because of the regimentation that they carry with them from their prior learning environment.

Property #9: One of the gripes about the U.S. educational system is that when viewed “from above” (at the national, state, or even school district scale) there is variation in the quality and success rate within each particular scale. Some of the spatial patterns we see show differences between inner-cities, suburbs and rural areas. Some of the geographical patterns we see show differences between states, e.g. low performing southern states versus higher performing states in the upper Midwest, Pacific Coast and parts of the Northeast. The current approach toward reform—that is, smoothing out and improving the overall pattern—takes two strategies. On the one hand, reform seeks to establish national standards which all states, school districts, and schools are encouraged to adopt. The idea here is that—in a democracy—all kids should have the opportunity to learn the same things. On the other hand, reform seeks to identify those districts, schools, teachers, and students that are underperforming, with the (supposed) intent of targeting extra resources to helping those who are lagging behind. (Of course, under No Child Left Behind annual assessments become part of a benchmarking strategy that targets schools, teachers and administrators for closure and termination.) This second reform strategy recognizes that the entire system cannot be fixed all at once but has to be dealt with incrementally. Notably, many observers in places that are “doing well” (comparatively speaking) say that they really do not need “fixing”—and this is one reason why the debate regarding national standards is so intense.

How might the other seven properties of infrastructure be used to understand educational systems?

Interesting perspective, Anne RT @geodoctress: New blog post on #education as #infrastructure. https://t.co/wgIYLNNuvl